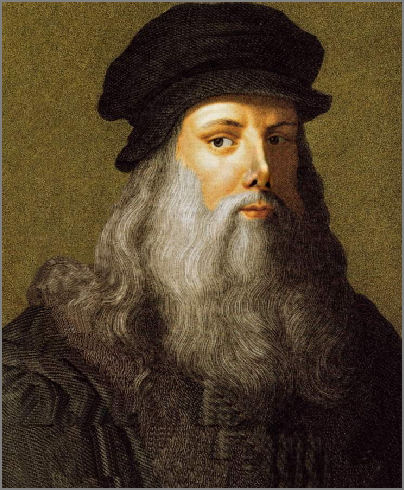

The Laocoön is widely recognised as a masterpiece of the last years of El Greco’s life and I find it so fascinating. It is a free and vigorous piece of work, showing the emotional charge and power of the works that El Greco created between 1610 and 1614.

This is El Greco’s only extant painting of a classical mythological subject and no work by him has aroused so much controversy among scholars. Despite numerous attempts to interpret it, no consensus has been reached about its meaning. It has been suggested that perhaps it is simply a straightforward depiction of the legend but because El Greco was known for his formal and iconographic inventiveness, it is arguable that there are additional layers of meaning here.

There are several versions of the legend of Laocoön and his sons. The account in the Aeneid is undoubtedly the best known version. According to Virgil, Laocoön, a Trojan priest in the service of Neptune (Poseidon), incurred the wrath of Minerva (Athena) by throwing a spear at the wooden horse that she helped the Greeks build. In retaliation, Minerva sent serpents to kill him and his sons as he offered a sacrifice to Neptune later in the day. The Trojans interpreted these deaths as an omen that the horse should be brought into the city.

It has also been suggested that El Greco based his painting on the pre-Virgilian account of Arctinus of Miletus. According to Arctinus, Laocoön was a priest of Apollo, who required chastity from those in his service. Arctinus asserted that Apollo ordained the death of Laocoön to punish him from marrying and fathering children. It is said that the figure struggling with the serpent on a far left of the painting represents the son who escaped from death according to Arctinus’ account. However, because the serpent’s head almost touches this figure, it is difficult to believe that El Greco intended to suggest that this son will escape death.

El Greco could also have been familiar with the accounts of these deaths in the commentaries on the Aeneid by Hyginus and Servius. Both authors maintained that Laocoön served Apollo and that he had been chosen by lot to offer a sacrifice at Neptune’s altar. According to Hyginus, Apollo had been previously angered by the priest’s marriage and took advantage of the ceremony at Neptune’s altar to send serpents to attack him and his sons. Servius states that Apollo was particularly angry because Laocoön had had intercourse with his wife immediately before he offered the sacrifice at Neptune’s altar, but both Hyginus and Servius agreed with Virgil that the serpents killed both of the sons.

There is argument which suggests that this is an unfinished work and that it is this which makes it difficult to identify what the relationship is to the two figures at the right of the painting. In the background is a free representation of Toledo, with the wooden horse standing in front of the Puerta Nueva de Bisagra.

Given the debate about the meaning of the painting, it is probable that El Greco wanted the painting to serve as a warning against the violation of the now of chastity as this accords with the mood of the Church in Toledo during the Counter-Reformation. The Council of Trent maintained that the failure of priests to observe the vow of chastity discredited the Church and thereby made people susceptible to the corrupting influence of Protestant beliefs.

As to the ‘unidentified figures’ it is suggested that the male figure represents Apollo as he would have been a logical witness to the execution that he ordered. The figure appears to have a raised arm as a gesture of presentation or command, both of which would have been appropriate for Apollo in this circumstances. The representation of Apollo as a young man posed in this way also is representative of the classical tradition.

The female figure may have been Venus (Aphrodite) as the goddess of love played an important role in the entire history of the Trojan conflict.

Whatever the interpretation, this is a powerful piece and the elusiveness of its meaning adds to both its power and mystery. I never tire of revisiting this painting, as with most of El Greco’s work.

It is worth noting that the painting was cleaned and restored by Mario Modestini in 1955. Extensive areas of loss in the throat, chest and legs of the figure at the far left and in the raised leg of Laocoön were inpainted,as were smaller scattered damages. Modestini removed loincloths which had been painted over the figures at the far left and far right and a large bouffant coiffure which had been added to the female figure at the right. He also exposed the middle head of the group of three now visible at the right and the fifth leg between the two standing figures at the right. (See image below).