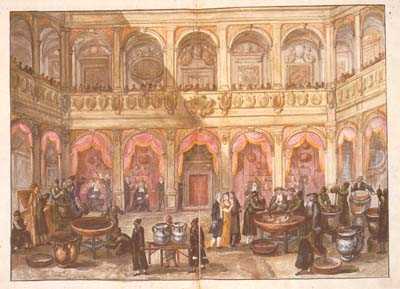

(Water colour by Domenicao Ramponi 1818 – Preparation in the courtyard of the Archiginnasio at the end of the 18th century.)

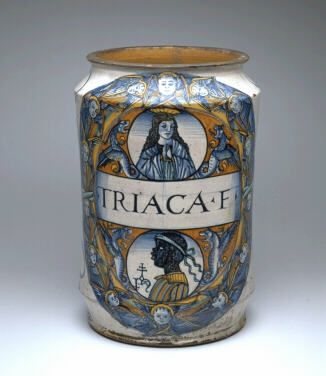

Teriaca – a miraculous potion

The legend goes that, in the second century BC, a physician-poet named Nicandre living in Colophon (Ionia) wrote a poem entitled Ta Theriaca. This treatise on the treatment of bites from wild animals, in particular serpents and other poisonous creatures, took its name from the Greek work therion [literally ‘viper’ or ‘serpent’, and by extension “poison” in general].

In 65BC, Mithridates, King of Pontus (the Black Sea coastal region in the north-east of present-day Turkey) brewed the famous potion for the first time. Totally 45 ingredients, the recipe was them completed by Andromachus, personal physician to Nero, who added a further 25 substances. Criton, physician to Trajan, then coined the name Teriaca, and the philosopher/physician Claudius Galenus (131-201) was responsible for establishing its reputation.

As it developed over the years to follow, a whole host of recipes were concocted, generally changing according to the city where the potion was produced: Paris, Venice, Strasbourg, Poitiers or elsewhere. Amongst the recurrent – or most extravagant – ingredients that might be cited: powdered viper (made from live vipers), opium, dried wine lees, powdered stag’s testicle, the horn of a unicorn [in fact, a narwhal] and so on.

The claims made for the portion were infinite. Some of the things it was said to heal were: the plague and all infectious diseases; scorpion stings; viper and rabid dog bites; tuberculosis; putrid fever; stomach ailments; sight defects… By the 17th century, Venice had established a Europe-wide reputation for its own Teriaca, produced under the supervision of the State health authority and then exported not only throughout Europe but even to Turkey and Armenia.

Such success inevitably stimulated greed, with some Venetian monasteries – for example, that of Santi Giovanni Paolo – taking advantage of the fact that they were not under State control to produce vast quantities of the stuff. Even more seriously, there were ‘fakes’ either of the product itself or of the label and packaging under which it was sold. This could lead to the apparently legal exportation of potions that were either inefficacious or even dangerous. A victim of the abuses arising from its own success Teriaca ceased production in the 19th century.

(Adapted from Secret Venice by Jonglez Zoffoli)