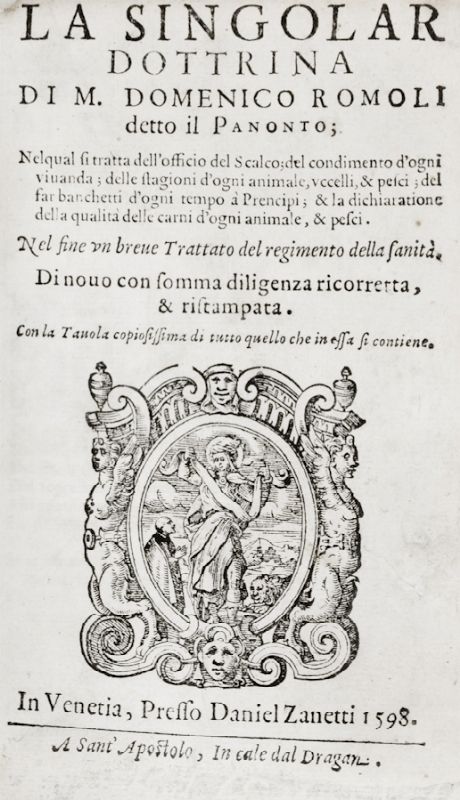

Domenico Romoli, a contemporary of Bartolomeo Scappi (see a previous blog entry), first had published in 1560 his Singolare dottrina which was an accumulation, much like Scappi’s work, of his professional knowledge and wisdom in the keeping of a house. In Book 1 of this work which he is writing to a younger man, Francesco a would-be steward, he discusses the role of the personal or private cook and the responsibilities of the steward of the house with respect to the cook. It makes very interesting reading…..

“You should be aware of and keep a vigilant eye on everything that concerns your lord’s food, and above all else you must order that the Kitchen, the Credenza and the Personal Provisioning Office behave in a way a miser watches his treasury…”

I sometimes ponder how very important an individual is who is a personal officer of noble Princes since in the face of so many dangers they place their life in his hands. The Cook is one of the foremost of those officers, and I used to shudder when I held the office that you aspire to, and now give God the most heartfelt thanks for having seen me through it honourably. In truth it is one of the most care-racked offices that can be imagined, because you have constantly to keep your eyes wide open: in striving to do your duty and to avoid any mishap, you must always have your mind on the dangers around you. To exercise the function properly you have to arm yourself with a shield rich in charity, faith and dedication.

To get back to what we were saying, after having found a Provisioner you must next secure a good and worthy Cook, one who, like an old physician, has grown old in his art. Above all, have nothing to do with a drunkard, even if he were the most outstanding master cook in all the world: for, rather than cooking the foods as you need to serve them, he will have cooked the main dishes before the appetizers. I warn you because it has often happened to me; so be careful. What goes on in the kitchen is supremely demanding, exhausting and exasperating, and for that reason an older person cannot stand it for long; you should give him a suitable young man, trained by him or a colleague, as deputy cook. The assistants should be experienced and the scullions clean – with instruction you can insist on their being neat and clean. You will supply them with fine and coarse cloth and aprons. You will constantly require them to be clean-shaven, to have their hair closely trimmed, to have their white blouses tucked into their aprons, their clothing short, clean and snug. Mind that they are not snotty nor have pimples and pustules. They should not be quarrelsome but obedient, civil, cheerful and, as much as possible, Italian rather than foreigners.

When their dishes are all prepared and you are ready to begin serving them, he will have them thoroughly clean the little table where their work will be dished up. He will also have them set out on it everything that is needed, both morning an evening, such as lemons, oranges, cheeses and candies, and the master’s caddy of spiced candy. And he will have his clean knives and your serviette around a clean loaf of bread set out for the usual proving of dishes and sauces, and a medium-sized iron fork.

In particular, you should keep the Cook cheerful, though not with that cheer that comes form too much drinking, as I said.

…

I should like to see you and your Cook take great pains to become thoroughly familiar with your master’s taste because it is apparent that some masters do not like spices, or cheese, or sweet things, or bitter things. Likewise you should know what his fixed, usual hour for meals is, both morning and night. Clearly, a gentleman’s appetite is hard to determine, because in most cases it tends to be whimsical; but you have to be as assiduous as you can, for in this business a person must be more a diviner than a steward. When you cannot guess their meal times it is no wonder that they are badly served, because prepared dishes and appetizers dry out, sauces and soups are spoiled, boiled things get cold and roasted things get tough in the warming pans. But I tell you, if you know the set meals time you will not go wrong. You will have to watch that the small appetizers don’t get overcooked – they’ll be done while you are setting up the table; big roasts can be kept on the spit until serving time. That way your honour will not suffer and your master will be pleased at how good all your dishes are when they have been well prepared by that worthy Cook.”

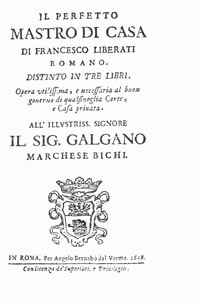

Similarly Francesco Liberati in his Il perfetto maestro di casa (1670) wrote in similar terms…

“The Personal Cook serves the Prince’s board and must be off in a kitchen square from the common one of the household; that office is so important that neither the Steward or the Major-Domo can visit it if it is not convenient. In choosing him, there must be information about his capability and his trustworthiness. It is advisable that the cook not be from a distant land – thought, if he is, he should have lived for a long time with women in the Master’s province. In the matter of cooking he needs to be experienced with pasta dishes, with jellies, plain boiled dishes, broths, pastries, potages and everything else touching on his service. He must avoid consuming a great amount of wood, coal, spices, fats and similar ingredients than in required by the job; and taking the leftovers for himself under the pretext of payment in kind – which is not permitted, and all the less so are ashes and used frying oil, because the frying pan is not refilled every time – those things being distributed, the ashes to the laundry, the frying oil to the kitchen lighting service, so saving both oil and candles. That office must be clean, and cleanliness lies not only with the person and dress but also in the kitchen and the equipment, by cleaning copperware, pewter, tables, spits and everything else. It is not for outsiders to come into the private kitchen, nor are cooks there allowed the number of scullery boys that are usually found in similar places, both for the sake of cleanliness and because of accidents that can happen with them.”

(Adapted from The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570) as translated with commentary by Terence Scully)