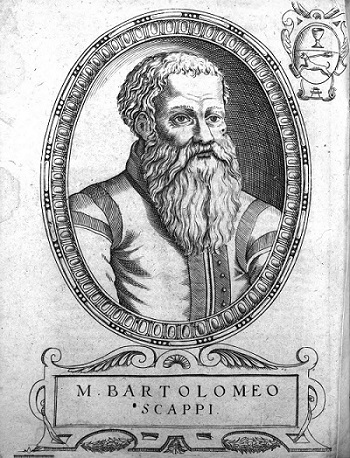

If you visit the Museo di Palazzo Poggi, Bologna’s main university museum, you will discover a room dedicated to the work of a 16th century naturalist, Ulisse Aldrovandi, where you will see some of the ‘18,000 varieties of unusual things’ he claimed to have accumulated. Many of his pieces have been lost or were sold during the positivist 19th century, but this collection will give you a wonderful insight into this extraordinary and endlessly curious genius.

Ulisse was born in 1522 into a middle-class family. His father was the secretary to the Bolognese Senate. From an early age it is said that he displayed a spirit of restlessness and curiosity, and at age 12 he ran away to Rome, only returning 4 months later giving into the pleas of his widowed mother to return. By age 14, he was put to work as a bookkeeper’s assistant but a year later, he departed again, this time on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela and the Galacian promontory known as Finisterre, but the difficulty of the journey forced him to turn back.

In 1539, back in Bologna, he embarked on a degree in law and the humanities, but before qualifying as a lawyer, headed to Padua. where he studied philosophy, maths and medicine. Returning to Bologna some three years later, he was accused of heresy together with a group of other academics and free-thinkers – it was the time of the Counter-Reformation – and although it is not known what the exact charges were it was doubtless some deviation of thought from Catholic dogma that got him in to trouble.

Fortunately for him, Pope Paul III died at the end of 1549 and the heresy case ended, but during his time awaiting trial in Rome, he studied classical antiquities and struck up a friendship with Guillaume Rondelet, a French doctor, with whom he found a mutual interest in botany and zoology. Inspired by Rondelet’s work, Ulisse began collecting preserved fish and other sealife specimens, which became the foundation of his extensive collection.

In the early 1550s he obtained a doctorate in Bologna in philosophy and medicine and was made a professor of natural history at the university, a post he held until his retirement in 1600. During this time he established a scientifically-organised botanical garden which still exits today.

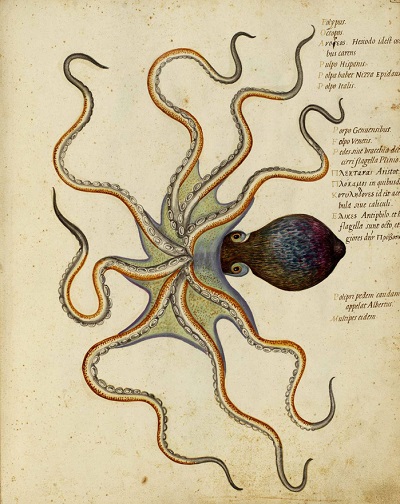

As he aged, his travelling become less and less but he corresponded extensively with other scientists and collectors and engaged people, including missionaries to bring back rare and beautiful items for his personal collection and for this “Theatre of Nature” which he had begun to assemble. He also commissioned a series of magnificent line drawings and watercolours of items in his collection from leading artists of the day, while woodblocks of his work were also made. He also left a vast collection of dried and pressed plants.

He eventually produced some 17 volumes of illustrations including the 4 volume Storia Naturale which he began in his 70s and only completed shortly before his death at 83 – a three volume Ornithologiae and a volume dedicated to insects, De animalibus insectis. After his death his widow, students and assistants took up the baton to continue his work and the final volume Dendrologiae (1667) was curated by two scholars who had not even been born in his lifetime.

Some of his more extraordinary pieces include a giant toad with a crude tail attached to it by a creative taxidermist, and a shark that was modified and passed off as a much rarer species. More famously, there is the ‘dragon’ which was caught near Bologna in the very day in 1572 that the ‘Bolognese Pope’ Gregory XIII was being invested in his home town. This dragon was seen to be a ‘portent’ and gifted to Aldrovandi by his brother-in-law Orazio Fontana. Although the specimen no longer exists, there is a woodcut of Drago aethiopicus.

Other strange ‘fakes’ circulated at the time, but there is nothing to suggested that he was complicit in their creation, rather there was considerable money to be made from collectors who wanted composite animals!

He outlived all this children so his entire collection was left to the city of Bologna, so that it might ‘aid and benefit man’.

There is no doubt that the illustrations of his collections are beautiful and what remains of his collection at the Mueso Ulisse Aldrovandi in Bologna is really an extraordinary experience to see. One cannot fail to be intrigued and amazed by the scope and depth of the desire for knowledge that this amazing man had and the gift he left the world.