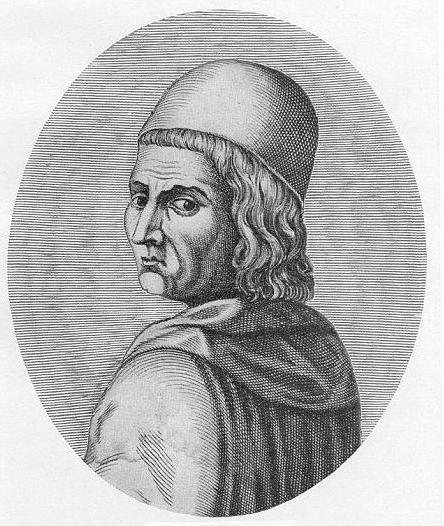

The fine Renaissance Palazzo Carafa holds a copy of the horse’s head originally exhibited in Naples National Archeological Museum in the 18th century. Considered as a symbol of the city, the provenance of the head has always been disputed: some have seen it as a Greek original while others (including 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari) attributed it to Donatello. Since 2012, archival documents have confirmed the second hypothesis.

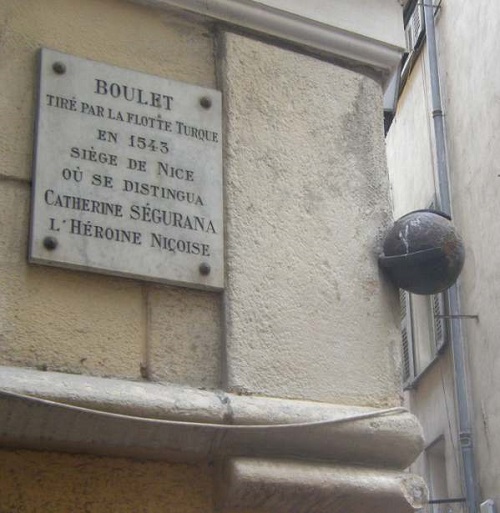

Before it was deleted, this inscription could be read on the base on which the sculpture now rests:

This head shows

All the nobility and immensity of his body,

A barbarian forced the bit on me

Superstition and greed put me to death

The regrets of the good increased my value

Here you see my head

The cathedral bells keep my body

The symbol of the city perished with me…

There is a rumour that on some days a horse is heard whinnying when the cathedral bells ring out. Be that as it may, this horse is legendary.

Until the 14th century, in a square near the cathedral stood a huge bronze horse that had the power to heal sick animals, give immunity to healthy ones and increase the fertility of males. The bronze was thought to have been carved by Virgil, who later placed it on this site.

For centuries, Neopolitans would bring along their beasts, harnesses hung with little crescent loaves and garlands of flowers, to have them walk three times around the monument. According to Virgil’s biographer Donatus, the loaves evoked the symbolic bread that Emperor Augustus gave Virgil when the poet cured several of his horses of a mysterious ailment.

This ritual lasted until 1322, the year when the body of the statue was destroyed, in line with the Angevin monarchs’ determination to eradicate all traces of pagan beliefs.

The legend goes that it was a cardinal, annoyed by this horse that was more popular that Saint Januarius, who had the bronze melted down to make the cathedral bells. Another version blames the blacksmiths, who were envious of the horse’s powers that stopped them from making a living.

The free and unrestrained horse is one of the most significant and persistent symbols in Neopolitan mythology. The people saw themselves in this untamed bronze horse, as borne out when two of the city’s conquerors, Conrad of Swabia (1253) and Charles of Anjou(1266), had a bit fitted to the horse to ratify their conquest and point out to the Neopolitan rebels that they had to submit to Christianity.

Once the horse was gone, the cult moved to the church of Sant’Eligio Maggiore (Saint Eligius, protector of balcksmiths). On 1 December, unshod horses were brought in and their shoes hung on doors. Gradually, Saint Eligius) was replaced by Saint Anthony the Abbot, whose church was built in the district named after him during the Angevin period. This saint has the power to heal all the animals and on 17 January, his feast day, a number are bought to the priest to be blessed. Until some forty years ago, the animals were dressed up in the kind of finery worn at the time of the bronze horse and, as before, they turned three times around the church…

The blessing of the horses also exorcises the dangers of travel: once horses were no longer used as a means of transport, all kinds of vehicles continued to be blessed. The ritual is still practiced today but in a very low-key fashion.

Until the 18th century, the horse was the emblem of two neighbourhoods: Nilo and Porto Capuana. The first was black, the second white. They symbolised the darkness and the light, black on the left and white on the right (facing the city, back to the sea), exactly as the Moon and the Sun frame the Madonna of Piedigrotta (see a post to follow).

(Adapted from Secret Naples by Valerio Ceva Grimaldi and Maria Franchini, published by Jonglez)