Corsica is a veritable paradise of distillers, macerators, mixers and blenders, and nature has bestowed on them an abundance of lemons, seedless tangerines, oranges, cherries, figs, myrtle berries and, of course, grapes.

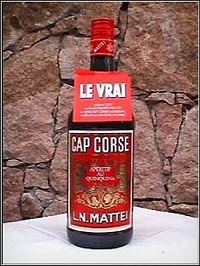

In the 16th century, when Corsican Muscadets were causing something of a furore in Italy, the islanders began to macerate the local fruit in brandy, Production was unexpectedly and dramatically increased at the beginning of the 19th century, when the island received its first stills. and since the haute monde of France (which had acquired Corsica from Genoa in 1768) simply adored liqueurs of all kinds, the islanders were quick to capitalise. Soon each village had its stills and each family developed its own recipes for a variety of aperitifs and ‘soothing potions’. Fruit farmers and vintners were particularly inventive, creating a variety of elixirs and developing increasingly complicated production methods. For example, they macerated the fruit in wine spirits, and then distilled the extract to obtain a colourless aromatic concentrate. Rosé wines were used as a base for many of these drinks, the most famous of which was Vin du Cap Corse from Quinquina, created in 1872 by Loius Napoléon Mattei. As with Dubonnet and Byrrh, its close relatives on the French mainland, this was aimed primarily at soldiers who were sent overseas on duty. It was intended as a pleasant way for them to take cinchona (or Peruvian bark), the ‘miracle product’ for medicinal purposes, and to offer them protection against fevers and stomach upsets.

The Mattei company grew to become one of the island’s leading providers of alcoholic drinks, but there are also a number of smaller companies, including Orsini, which have made names for themselves as producers of specialties.

Corsican elixirs

Cap Corse – the most famous aperitif made from grape must, only from Appellation Cap Corse, which has been ‘silenced’ by the addition of wine spirit. It is flavoured with 17 different plant essences, including gentian, cocoa bean, Seville oranges, vanilla extract and cinchona bark. It was extremely popular in France and overseas at the time of the Belle Epoque. Best drunk chilled but without ice, as a Marseillaise, which is two parts Cap Corse and one part lemonade.

Cédratine – In 1880, Mattei marketed a liqueur under the name of Cédratine, which owed its intense aroma of lemon an cedar to the citron, thereby continuing a centuries old tradition. The peel is left to macerate in wine spirits for a year, after which time the extract is distilled. the basic liqueur – syrup and alcohol – is then flavoured with the distillate. Best drunk chilled.

Bonapartine – In 1920, Mattei registered another product, a liqueur made from oranges and mandarins, which is 22 percent proof. Other producers make a simple Liqueur d’Orange, which is made from orange peel macerated in wine spirits, distilled and mixed with syrup as well as other plant and spice extracts.

Liqueur de myrte – The berries, which are picked on the maquis, are left to dry for three weeks and then steeped in alcohol, A concentrated syrup is then added after a 40 day maceration period, and the resulting liqueur is purple in colour, It is filtered, bottled, and stored for a period of time. If the berries are distilled, the liqueur is colourless. These basic recipes are frequently varied by other manufacturers as well as private families using old family recipes.

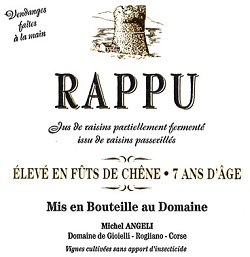

Rappu – This is made mainly in Patrimonio and is a blend of Grenache, Aleatico, and Alicante. The grapes are left on the wine until they are ripe to increase the sugar content, and then they are mashed together with the stalks, whichis what gives Rappu its typical flavour. The vintners then leave the must to ferment. When about 100g of residual sugar is left, they stop the fermentation process by adding young brandy. Left in a barrel to age, the liqueur takes on the colour of mahogany, and takes on the aroma of stewed fruit, toast, and caramel.

Eau-de-vie de châtaigne – This is a highly unusual schnapps made from chestnuts. First the chestnuts are ground, then steeped. They are left to ferment and then distilled. Each distiller has his own recipe, to suit whichever of the 50 or so different types of chestnuts he has.

Vins de fruits – There are a number of fruit wines made on Corsica, generally using citrus fruit, wild cherries, vineyard peaches and wild arbutus which are the preferred choices. The fruit is steeped in wine spirits and left to macerate for three months or longer. The highly aromatic alcohol is then filtered, mixed with rosé and finally sweetened with sugar,

(Adapted in part from Culinara – France)