Nikola Božidarević, Dubrovnik’s most famous painter only ever signed himself twice on his preserved paintings – as Nicolas Rhagusinus and Nicolo Raguseo – so his true identity was only discovered some two centuries after his death. His father Božidar Vlatković was himself a skilled painter with his own workshop in Dubrovnik and no doubt had a significant impact on shaping his son’s skill.

Nikola was born c.1463 and on 2 September 1476 was apprenticed to the Ragusan painter Petar Ognjanović, who promised to house, feed and teach him, and at the end of this apprenticeship to give him 10 hyperperi, a cloak and the tools of his trade. However, on 6 January 1477, the contract was annulled by mutual agreement so that Nikola could travel to Venice and not until 1491 does he reappear in Ragusan records. There is little to indicate what he was doing in those intervening seventeen years. Some have suggested that he worked with the masters of Murano, and it is clear that he was strongly influenced by the works of Carpaccio, as well as Carlo and Vittorio Crivelli. It has also been suggested that he knew the fresco work of Perugino and Pinturricchio in Rome.

After he returned to Dubrovnik, he and his father worked jointly on commissions – a large polyptych for the Gradić family intended for the Dubrovnik Dominican Church (1494) and later the triptych for the Bundić family chapel in the same Dominican church (c.1500).

This latter triptych shows both the influence of Renaissance Venice and of the masters of Ancona. The painting is marked by its strong symmetry which was particularly prized by Ragusan patrons. On each side are two heavily bearded, mitre-wearing saints (St Blaise and St Augustine) standing beside two shaven-headed saints (St Paul and St Thomas Aquinas). The Madonna and Child are the focus of the central panel. Below the Virgin is an upturned crescent moon (echoing the Book of the Apocalypse 12:1). St Blaise holds in his hands a model of early sixteenth century Dubrovnik, which remains to this day, the best indication of how the city looked at the time. The harbour, securely protected by chains and breakwater, is full of ships, while figures on foot and horseback can be seen. The painting can also be dated by observation of the exact stage of construction of the Great Arsenal. (See above).

During the first decade of the sixteenth century he received a series of important commissions, including in 1501, the upper part of the altarpiece in the Dubrovnik Franciscan church. In 1504 he painted a large triptych for the cathedral and in 1508 another triptych in the cathedral dedicated to St Nicholas. In 1501 he painted a large portrait of St Jerome, dressed as a cardinal, for the Rector’s Palace.

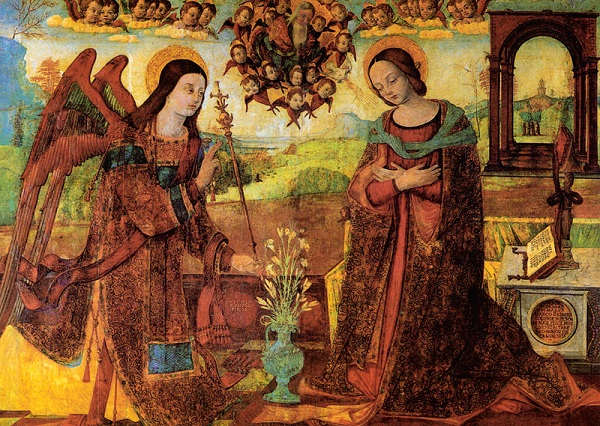

By now, he was the head of a large workshop and increasingly used collaborators to fulfil his increasing number of commissions. His second extant work was painted in 1513 for the Dominican Church in Lopud which was commissioned by the Lopud seacaptain Marko Kolendić. The main body of the painting is given over to the Annunciation, with the idealised landscape behind the Virgin and the Angel Gabriel having far greater depth than had ever been seen before in paintings in Dubrovnik.

In 1517, just before his death he completed the last of his four preserved works – the altar painting in the form of a triptych for Our Lady’s Church at Dance. This work was criticised as being more conservative with a liberal application of gold, The work featured not only the Madonna and Child but a lunette depicting the crucified Christ surrounded by female saints, an image St George slaying the Dragon, as well as panels showing the papal coronation of St Gregory and the episcopal coronation of St Martin.

Nikola Božidarević died towards the end of 1517 while he was still working on a large polytych for Dubrovnik Cathedral. He was by that time a rich man, he had never married, but was survived by his father.

It has been said that it is impossible to decipher his true personality from his paintings, which are characteristically lyrical and almost dreamlike. Irrespective of his true nature or personality, he contributed significantly to the body of Renaissance art in Dubrovnik and should be appropriately recognised and remembered for this contribution.

(Adapted in part from Dubrovnik – A History by Robin Harris)