Cradled in a majestic circle of Alps, the Vallée des Merveilles in the Mercantour National Park, Provence is aptly named. It is a landscape of rock-strewn valleys, jagged peaks and eerie lakes.

Just west of the Lac des Mèsches is the Minière de la Vallaure, an abandoned mine quarried from pre-Roman times to the 1930s. Prospectors came in search of gold and silver but had to settle for copper, zinc, iron and lead. The Romans were beaten to the valley by Bronze Age settlers who carved mysterious symbols on the polished rock. ice-smoothed by glaciation. These carvings were first recorded in the 17th century but investigated only from 1879, by Clarence Bicknell, an English naturalist. He made it his life’s work to chart the carvings, and died in a valley refuge in 1918.

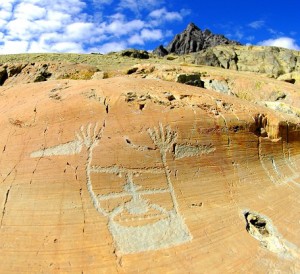

The rock carvings are similar to ones found in northern Italy, notably those in the Camerino Valley near Bergamo. However, the French carvings are exceptional in that they depict a race of shepherds rather than hunters. The scarcity of wild game in the region forced the Bronze Age tribes to turn to agriculture and cattle-raising. Carvings of yokes, harnesses and tools depict a pastoral civilization, and these primitive inscriptions may have served as territorial markers for the tribes in the area. Whatever their meaning, this is the largest site of rock art in Europe.

However, the drawings are open to less earthbound interpretations. Anthropomorphic figures represent not only domestic animals and chief tribesmen but also dancers, devils, sorcerers and gods. Some are said to represent a ‘divine primordial couple; the ‘earth’ goddess who is impregnated by the storm god, Taurus. Such magical totems are in keeping with Mont Bégo’s reputation as a sacred spot (shepherds working in the valleys below more than 3,000 years ago treated Mont Bègo like a temple, a place where sheep were sacrificed to appease terrifying storms). Given the bleak terrain, it is not surprising that the early shepherds looked heaven-wards for help. Now as then, animals graze by the lower lakes. However, the abandoned stone farms and shepherds’ bothies attest to the unprofitability of mountain farming.

Seeing the carvings

The Vallée des Merveilles is accessible only by four-wheel drive or on foot, and now, due to vandalism, certain areas can only be visited with an official guide. However, there is also a signposted footpath that leads visitors to some carvings without a guide;; it begins at Lac des Mèsches car park and is a seven-hour round trip. Given the mountain conditions, the drawings are only visible between the end of June and October. If is an 8km (4 mile) drive west from St-Dalmas to the Lac des Mèsches. In the nearby town of Tende you can visit the Musée des Merveilles. A signposted path can also be found on the eastern side of Mont Bégo in the Fontanalbe valley, which again is accessible to visitors without a guide; there are 280 carvings along what is called the ‘sacred route’.

So next time you are visiting Provence, you may want to take the time to take the walk to see these amazing rock carvings in a truly magnificent valley.