(Unknown Florentine Painter: Leon Battista Alberti, early 17th century, oil on canvas 63 x 45cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

Leon Battista Alberti was born an illegitimate, albeit recognized son, of one of the most high-ranking and wealthiest Florentine families. He received a comprehensive education, and obtained his doctorate in law at the age of just 24 in Bologna, which at the time had one of the most famous universities in Italy. By the age of 20, he had written the comedy Philodoxeos; later he took up the study of mathematics and the natural sciences. Although Alberti tried his hand at painting and sculpture, he ultimately remained a theoretician. Even in his work as an architect he contented himself with producing designs and models of various projects, preferring to leave the practical execution of the buildings to others with greater aptitude.

The importance of Leon Battista Alberti in each of his various endeavours as a humanist, poet, art theoretician and architect is equally great and impossible to overestimate. This universal scholar of the Italian Renaissance was intimately acquainted with the most important humanists, artists, popes and regents of his time period. His versatility can only be compared to that of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and Michelangelo (1475-1564), but these two lived in later times and were able to build on Alberti’s basic ideas.

Alberti, by virtue of his treatises on painting and sculpture, the Elementi di Pittura (“Elements of Painting”), a Statua (“Sculpture”) and Della Pittura Libri III (“About Painting, Book III), which appeared in 1434-35, provided the Renaissance with its first scientifically-based theoretical foundation or art and art history.

In his first book, Alberti gives an explanation of perspective based on his own extensive observations in the fields of geometry and optics. He defines painting as a “projection of lines and colours onto a surface”, and insists that artists have a knowledge of poetry and rhetoric as well as a certain amount of general knowledge so as to be able to render their subject appropriately. This methodical approach was very innovative, as older treatises, such as that written in about 1390 by Cennino Cennini tended to concentrate on more practical instructions for the artist.

In contrast, Alberti elevates art beyond the level of a craft to a science, thus reflecting the newly developed humanistic approach to art, which Alberti, himself embodied as the ideal uomo universale (“Renaissance man”).

Besides his theoretical writings on how to paint and his exhaustive explanation of perspective, Alberti also describes in his treatises the appropriate criteria for evaluating a painting or other work of art. His fundamental ideas concern drawing contours, structuring a composition, and using colour. In his opinion, only the harmonious combination of all these factors could lead to a satisfactory result, To achieve this, he advises painters to be diligent in drawing studies from nature, The various parts of the body should correspond to one another in size, character, purpose and other qualities; for “…if in a picture the head is very large, the chest small and the body bloated, the composition would be sure to be ugly”. Finally, he singles out praise for his contemporaries Donatello, Ghiberti, Luca della Robbia and Masaccio, who, according to Alberti, were in a position to create great works of art using the new methods of the Renaissance after their long period of decline.

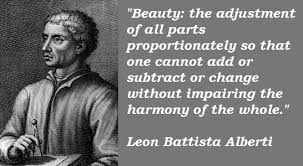

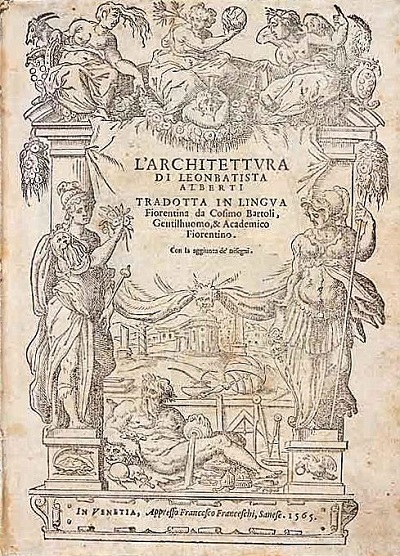

Around 1450, Alberti’s treatise on architecture, Dr re aedificatoria, was published. In it, he again turns to the theme of harmonious proportions, but applied to buildings rather than paintings. The treatise takes as its premise that beauty is the result of the harmonizing of all parts into a unified whole. According to Alberti, this is achieved by adhering to specific ratios, purposes and orders, according to the principle of proportion – which he claims is the most perfect and highest law of nature. Each part should be unified and independent, and at the same time echo the harmony of the whole.

The geometric design of the facade of the Santa Maria Novella in Florence is one of the best examples of Alberti’s theories of architecture in application, and particularly his revolutionary idea of connecting the narrower upper floor with the broader lower part of the church by the means of two huge volutes.

Much has been written about this extraordinary man, and for anyone interested in Renaissance art, then I do encourage you to read about Leon Battista Alberti and the profound influence he had on art and architecture.